🔒Now's the time to prepare for the post-quantum era

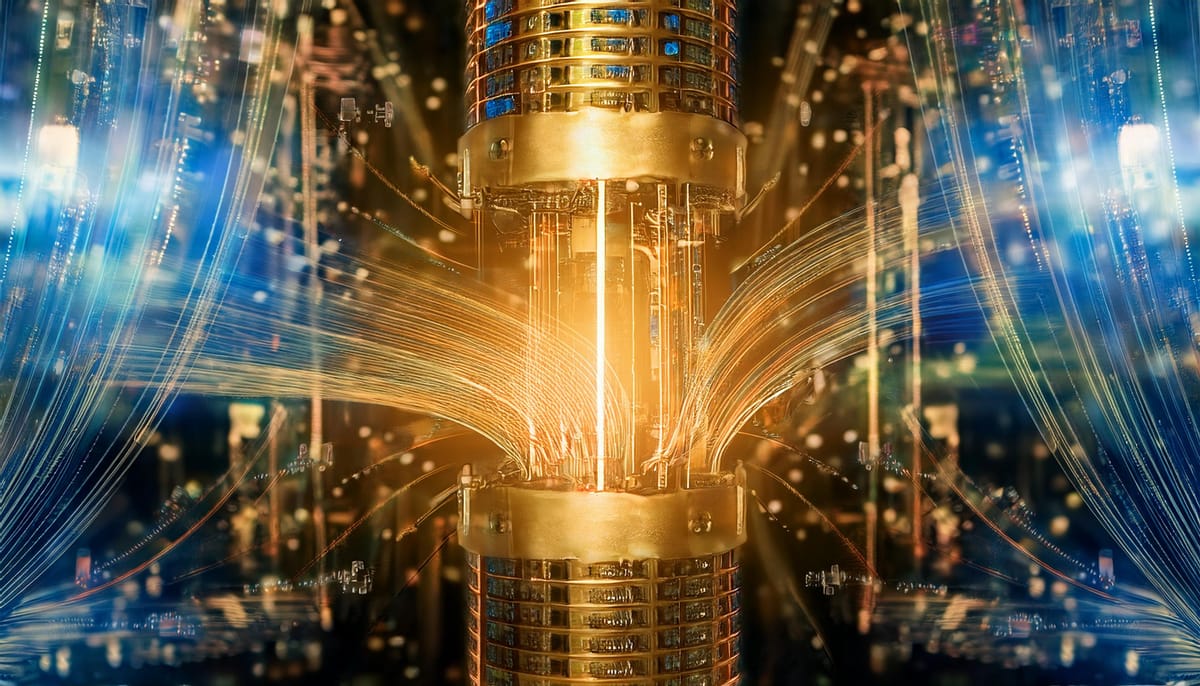

I've followed the development of quantum computing for the better part of the last decade. For the longest time, it's been "just around the corner" and with the advent of generative AI, any of the hype around the technology has receded into the background. But as with so many technologies, progress has been steady, with new error-correction techniques for building more durable, noise-resistant quantum circuits slowly making it out of the theoretical research arena and into the hardware.

IBM thinks it'll have a system with 1,000 logical qubits and low error rats ready to go in 2030. Earlier this summer, Ionq said it would be able to offer a system with 100 logical qubits next year (and a 1,000-qubit machine after that, which would then achieve "broad commercial advantage." Microsoft, which has been working closely with Quantinuum (all while working on building its own quantum computer), recently said that it believes a machine with 100 logical qubits could "potentially solve scientific problems that are unsolvable on classical machines."

All of this goes to show that there is now a reasonable chance that we will see useful quantum computers within the next five to ten years. And that has some interesting consequences for enterprises today: at some point in the not-so-distant future, quantum computers will be able to break the standard public-private cryptographic algorithms that secure virtually all data today.

A couple of months ago, I talked to Dario Gil, the director of research at IBM who is responsible for much of Big Blue's quantum computing program. IBM and others have long worked on creating post-quantum cryptography techniques that are hard to break for even the most powerful quantum computers.

Current encryption algorithms are secure because the calculations required to break them would take an impractically long time on traditional computers. But Shor's algorithm shows that it'll be easy for a quantum computer to break these security schemes. Exactly how many logical qubits it would take to break today's public-private key systems is up for debate, but chances are a machine with 2,000-3,000 stable qubits will likely suffice.

For my TechCrunch story, I talked to Dario about what this means for businesses today. After all, it'll take years -- if not decades -- to switch out all of the existing cryptography systems for ones that are resistant in a post-quantum world.

There's also another scenario to keep in mind: you can reasonably assume that if an adversary (and we're likely talking nation-states at this point) gains access to your encrypted data today, they won't be able to do much with it today, but if they hoard it, they'll be able to decrypt that information at some point.

This week, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published the first set of standards for post-quantum cryptography. Now that these are available, Gil argued, it's time for developers to start implementing them to replace the existing systems.

Ideally, there'll be drop-in replacements for existing libraries, but it probably won't be that easy – especially given the long tail of applications today that use encryption.

You can read my full story here.

Also from me this week

- Definity raises $4.5M as it looks to transform data application observability: a look at data observability startup Definity, which aims to give businesses better real-time insights into their data pipelines while their data is still in motion.

- I also had a fun conversation with the founders of CannonKeys, a mechanical keyboard company out of Providence, Rhode Island, founded by a former Microsoft and Klaviyo engineer.

A few weeks ago, CannonKey's CCO reached out to me and we met up for coffee in Portland. He brought along the company's latest keyboard, the Sat75 X, a fun, affordable keyboard with a cute little LCD screen. Building that board reminded me of how much fun it can be to build something physical again.

Full story here. - (Bonus: I also reviewed the Keychron K2 HE earlier this month)